Digital Transgender Archive

Pre-Colonial Gender Expression and Identity in “North America”

Authors: Julie Fiveash (Diné), Nick Metcalf (Sicangu Oyate), River Toomer (Tsalagi Freedman/ᏣᎳᎩ ᏣᏥᏲᏒᎢ) & Saylesh Wesley (Stó:lō/Tsimshian)

With special thanks to Shepherd Tsosie (Diné) and the Two-Spirit Archives Advisory Council for the Two-Spirit Archives at the University of Winnipeg

Indigenous* people continue to reclaim our systems, knowledge, worldview, and beliefs, which include the confluence of many gender expressions that are sacred. Indigenous languages maintain cosmological understandings that are lost when translated to non-white, non-heterosexual cultures and white American and European cultures. Gender in Indigenous societies interconnects with the Land and its ethical boundaries and The Spirit of the Land creates connections and interdependence with all Indigenous people. As such, humility keeps us smaller than ourselves and this relationship also connects us to the sacred. It is important to remember that Indigenous autonomy is bigger than just ourselves. Autonomy is sacred.

It should be emphasized that “cross-dressing was not always an indicator of cross-gender acting (taking on other gender roles and social status within the tribe). Lang explains, ‘the mere fact that a male wears women’s clothing does not say something about his role behavior, his gender status, or even his choice of partner…’. Often within tribes, a child’s gender was decided to depend on their inclination toward either masculine or feminine activities, or their intersex status” (Rainbow Resource Centre). Gender roles and gender expression in Indigenous cultures are not always assumed to be the same as a person’s identity.

Different forms of gender expression that existed were widely and violently extracted by colonizers who would enforce a strict gender binary. English terms were forced upon us and made us assimilate or conform to the colonizer’s norms as an act of survival. English terms can erase the difference between non-white, non-heterosexual cultures and white American and European cultures. However, creating our own terms using the colonial language allowed us to take up space in communities that have long ignored Indigenous peoples.

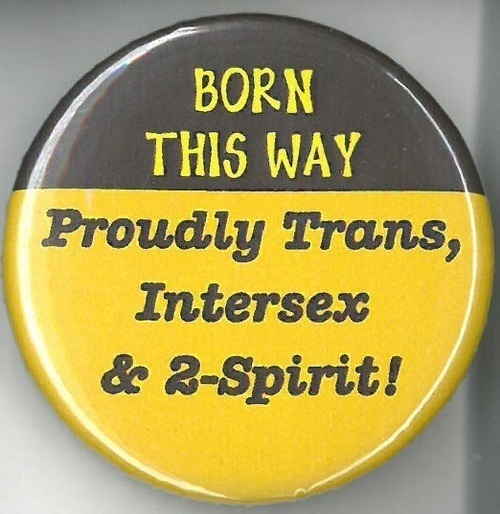

To begin embracing gender and sexuality outside of the cisnormative binary of our colonizers, we start with language and recognizing the limitations of vocabulary within a colonizing language. In the past, derogatory terms like “berdache”, “bardaje,” or “bardadj” were used by Spanish and French colonialists to describe any transfeminine Natives in the Americas (Rosario 16). This term was used often without any distinction between different tribal communities, lumping, for example, Diné and A:shwi “berdache” individuals together when describing them (Robinson 1677). Our beliefs about gender and sexuality were additionally extracted and eliminated from us in boarding and residential schools through the cutting of Native hair, enforcing gendered clothing, and other forms of forced assimilation into English culture (Hanson). This has led to it being difficult to find reliable, Indigenous-led research on gender expression in our cultures.

In light of this (or in spite of this), Indigenous people have been embracing ways of life that were stolen from us and in doing so, have been reclaiming our languages and the way we perceive ourselves in the language forced upon us. A common term was created for people outside of colonial gender and sexual expression within pan-Indigenous culture - Two-Spirit. The integral difference between the Two-Spirit identity and the western labels of LGBTQ+ is that it is not just a sexual or gender-based identity; it is a spiritual identity. “Two-Spirit, a translation of the Anishinaabemowin [Annishinaabe language] term niizh manidoowag, refers to a person who embodies both a masculine and feminine spirit. Activist Albert McLeod helped popularize the term after it was created in 1990 to broadly reference Indigenous peoples in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ)”(Filice). Albert McLeod has clarified that in the creation of the term, it was activist Myra Laramee who, at the end of July 1990, “had a vision where she was told the name for LGBTQIA+ people was Two-Spirits. Myra brought that name to the 3rd North American Gathering of Native Gays and Lesbians the first week of August [1990], and it was adopted at that time by the delegates who were from all over North America.”

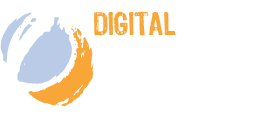

It is important to remember that the term Two-Spirit honors an Indigenous person’s identity outside the colonizer’s view of gender-nonconforming. “Two-Spirit” and “Non-Binary” are not synonymous terms. ”Two-spirit identity enables Indigenous people ‘to negotiate boundaries’ between bisexual, gay, lesbian, queer or trans communities and our own nations” (Brotman et al., 2002). “In gender and sexual minority settler communities, two-spirit identity makes Indigeneity visible and serves as a buffer against assimilation” (Robinson 1684). Non-Natives may feel that the term Two-Spirit is simply another term for gender outside of the binary but it is far more complex than that. White supremacy has taught us that gender relies on assigned identities and roles instead of personal knowledge. Expressing our true selves through appearance paired with language brings peace. It is an active way to honor ourselves in Western society.

It is important to remember that the term Two-Spirit honors an Indigenous person’s identity outside the colonizer’s view of gender-nonconforming. “Two-Spirit” and “Non-Binary” are not synonymous terms. ”Two-spirit identity enables Indigenous people ‘to negotiate boundaries’ between bisexual, gay, lesbian, queer or trans communities and our own nations” (Brotman et al., 2002). “In gender and sexual minority settler communities, two-spirit identity makes Indigeneity visible and serves as a buffer against assimilation” (Robinson 1684). Non-Natives may feel that the term Two-Spirit is simply another term for gender outside of the binary but it is far more complex than that. White supremacy has taught us that gender relies on assigned identities and roles instead of personal knowledge. Expressing our true selves through appearance paired with language brings peace. It is an active way to honor ourselves in Western society.

Two-Spirit culture is a mixture of our reconnection with Indigenous values around gender and sexuality and the modern Indigenous reality. It’s important to note that Two-Spirit—as an identity—can be viewed as transitory, or temporary, as not every LGBTQ+ Indigenous person chooses to adopt it. Two-Spirit is sometimes viewed as too broad to describe all the different Native identities that exist, as it is specific to the Anishinaabe language in its creation. Many Indigenous peoples choose to use their community-specific term over what they view as another culture’s term. In some cases, due to language loss or reconnecting to culture, Two-Spirit can be the identity an Indigenous person adopts for a period of time until they are introduced to their community-specific term. Other times, a person decides to use it in conjunction with their community-specific terms.

Ultimately, it is important to note that keeping Two-Spirit as an exclusive, Native-only term is an act of preservation. We are preserving a history that has faced genocide—through words, actions, and silence. Existing as Native and Two-Spirit is a declaration of honoring our ancestors and holding our ground against erasure from history. Our way of life has been threatened and creating our own terminology on how we see gender through a spiritual and emotional lens is a part of our healing process. Expressing our true selves through appearance paired with language and within community can bring peace.

Ultimately, it is important to note that keeping Two-Spirit as an exclusive, Native-only term is an act of preservation. We are preserving a history that has faced genocide—through words, actions, and silence. Existing as Native and Two-Spirit is a declaration of honoring our ancestors and holding our ground against erasure from history. Our way of life has been threatened and creating our own terminology on how we see gender through a spiritual and emotional lens is a part of our healing process. Expressing our true selves through appearance paired with language and within community can bring peace.

In compiling this page, there is much darkness that shapes who Two-Spirits / Indigiqueers have become and thus some of this is woven in; however, we have every intention to roll this out towards a more harmonious identity full of magic and connection. Understanding language or terms in our common tongue and the history of our ancestors and our interactions with gender, sexuality and self-expression helps us understand our own and can help us discover more. We hope to see Two-Spirit peoples continue to be brought into the larger conversations regarding Indigenous rights and that our history is not only maintained but embraced within the larger context of Indigenous peoples’ history.

*The term Indigenous will be used to describe the many Indigenous nations within “Canada,” “Mexico,” and “The United States”.

Indigenous Terms Glossary

Aboriginal: Term used to define Indigenous people in the land that is now known as Australia. “Aboriginal” is a retired term for the Indigenous peoples of Canada.

American Indian: A now semi-outdated term that was used to refer to Indigenous people in the United States; less likely to be found in texts after the 2010s, but is still used broadly in U.S.-based Indigenous organizations and the federal government. “Indian” is sometimes used as a shorthand.

First Nations: “traditional inhabitants in Canada prior to European contact (excluding the Arctic region) (Younging, 2018). There are currently over 40 unique First Nations and over 600 First Nations Bands recognized in what we now call Canada (Gray, 2011).” (from Indigenous Information Literacy)

Indigenous: Commonly used in global as well as local geographic contexts to refer to “original inhabitants from around the world.” (from Indigenous Information Literacy)

Inuit: “traditional Arctic inhabitants (including Canada, Alaska (USA), Greenland, and Siberia) (Younging, 2018) with over 50 communities (Gray, 2011).” (from Indigenous Information Literacy)

Métis: “Indigenous Peoples mixed with people who have European ancestors. This may include Métis people from the Red River Settlement and other settlements (Younging, 2018).” (from Indigenous Information Literacy)

Native American: A term commonly used to describe Indigenous groups within what is now known as the United States. “Native” is sometimes used as a shorthand.

Pan-Indigenous: “Presents a unified voice for Indigenous Peoples, but also homogenizes or reduces Indigenous diversity (Younging, 2018).” (from Indigenous Information Literacy)

Additional Resources

Organizations & Initiatives

- Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirits: https://www.baaits.org/home

- Native Justice Coalition, Two-Spirit Program: https://www.nativejustice.org/programs/twospirit/

- Paths Remembered, Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board: https://www.pathsremembered.org/

- Two-Spirit Dry Lab: https://twospiritdrylab.ca/

- Two-Spirited People of Manitoba: https://twospiritmanitoba.ca/

- Wabanaki Two-Spirit Alliance: https://w2sa.ca/

Videos & Websites

- Chacaby, Ma-Nee (Anishinaabe/Ojibwe-Cree). Author and Elder Ma-Nee Chacaby (Anishinaabe/Ojibwe-Cree) tells us about her grandmother’s affirmations and First Nations Two-Spirit people’s roles and positions outside of colonization. Ma-Nee Chacaby Talks About Two Spirit Identities.

- Harris, Sherenté (Narragansett). TEDTalk on his Two-Spirit identity and how it connects to dance. He dances Fancy Shawl at the end. Complete the Circle.

- Makokis, James (Nehiyô/Plains Cree). Dr. James Makokis is a Nehiyô (Plains Cree) Family Physician from the Saddle Lake Cree Nation who works with transgender and Two-Spirit teenagers on Kehewin Cree Reservation. This mini-documentary follows Alec, a Two-Spirit transmasculine teen. The documentary ends with beautiful stories shared inside a Two-Spirit sweat lodge. The Indigenous Doctor Helping Trans Youth.

- Metcalf, Nicholas (Sicangu Oyate). TEDTalk on their understanding and experience as a Two-Spirit person and gender identity adding to our world. Why We Need Gender Fluidity.

- Montiel, Anya. “LGBTQIA+ Pride and Two-Spirit People | Smithsonian Voices | National Museum of the American Indian Smithsonian Magazine.”June 23rd, 2021.

- Pruden, Harlan (Nehiyawe/First Nations Cree) and Se-ah-dom Edmo (Shoshone-Bannock, Nez Perce, Yakama). Slides from a presentation on Two-Spirit history and terminology. “Two-Spirit People: Sex, Gender & Sexuality in Historic and Contemporary Native America.”

- Roscoe, Will, “Sexual and Gender Diversity in Native America and the Pacific Islands.” from LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History. National Park Foundation. 2016.

- Tsosie, Shepherd (Diné). Personal website and blog. https://mydilbaadreams.com/.

Works Cited

“Aniyvwiya.” Cherokee English Dictionary, Internet Archive, archive.org/details/cherokeeenglishd0000feel/page/46/mode/2up. Accessed 23 Aug. 2022.

“Chahta Okla.” New Choctaw Dictionary = Chahta Anumpa Tosholi Himona, Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, 2016.

Filice, Michelle. "Two-Spirit". The Canadian Encyclopedia, 03 July 2020. www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/two-spirit.

Hanson, Eric, et al.“The Residential School System.” Indigenous Foundations. First Nations and Indigenous Studies UBC, 2020. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/the_residential_school_system/.

hooks, bell. (1997). "Representing Whiteness in the Black Imagination." In R. Frankenberg (Ed.), Displacing Whiteness: Essays in Social and Cultural Criticism (pp. 165–179). Duke University Press.

Robinson, Margaret (2020). "Two-Spirit Identity in a Time of Gender Fluidity," Journal of Homosexuality, 67:12, 1675-1690.

Rosario, Vernon. “Sex and Gender in Native America.” Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide, vol. 29, no. 4, July 2022, pp. 15–17.

Toran. “A LETTER TO WHITE PEOPLE USING THE TERM ‘TWO SPIRIT.’” White Noise Collective, 16 July 2019, https://www.conspireforchange.org/a-letter-to-white-people-using-the-term-two-spirit/.

Two-Spirit People of the First Nations - Rainbow Resource Centre. Rainbow Resource Centre, https://rainbowresourcecentre.org/files/16-08-Two-Spirit.pdf.